Whitewater and the Last Pandemic—the 1918 Influenza

Carol Cartwright, Whitewater Historical Society

Whitewater’s citizens are going through a tough time right now. Most of us are staying home while some workers carry on so the rest of us have essential services while keeping safe. We, literally, have never seen anything like this. But, we were due.

While the United States had some health epidemics, like polio, in the last 100 years, nothing has hit like Covid-19 since the fall of 1918, when another severe, highly contagious, new strain of influenza raced through the country in a matter of weeks. People called it the “Spanish Flu,” because they thought it came from Spain. It did not. No one knew where it really started, but traveling World War I soldiers had a large role in the spread of the disease.

The 1918 influenza virus had many similarities to Covid-19. It was highly contagious and often developed into pneumonia. Some people died within a couple of days of getting sick. Others fought a long respiratory battle and eventually recovered, while others just had severe flu.

The 1918 influenza virus was most severe in people in the prime of life, ages 19-42.

Older people fared better, suggesting that the flu was related to a less severe virus that older people may have had in the past. Like today, young children were not severely affected.

The new virus swept through army camps in the spring of 1918 and in September, there were 4,500 cases (including two men from Whitewater) and 100 deaths at the Great Lakes Naval Station near Chicago. Historians have concluded that the sailors at the Great Lakes Naval Station were the “super spreaders” of the influenza in the Midwest.

On October 10, the Whitewater Register ran four articles on the epidemic. The paper reported that there were 200 cases among the 3,200 residents of the city. And, many cases were reported in the “local” columns from rural towns such as Cold Spring, LaGrange, and Lima.

Guidelines for flu prevention were similar to advice given today. Citizens were told to avoid sick people, keep their hands clean and away from faces, not to spit in public, cover their noses and mouths if they sneeze or cough, and use clean handkerchiefs frequently (“Kleenex” not being invented until 1924). Because the 1918 virus was transmitted just like COVID-19, wearing masks was recommended and people were encouraged to make their own. And this stern warning was issued: if you have any type of sickness, stay away from people, go to bed, and isolate yourself in your home.

Wisconsin officials, in one of the few states that had a strong public health department, ordered churches, theaters, and public amusements closed, but it is unclear whether everyone complied, and businesses remained open. It was never officially announced in Whitewater that these rules were in effect.

Throughout October and into November, the Register printed many illnesses and deaths from the 1918 influenza. Stories about entire families having the flu were common. And, like today, health care workers were hit hard. A Whitewater woman, Mrs. Anna Pester, attended the funeral of Miss Emma Wegner who was a trained nurse in Milwaukee and died of influenza herself.

By the middle of November of 1918, flu cases had decreased in the area and in early December citizens were encouraged to go Christmas shopping in downtown Whitewater. But, it was too soon for people to congregate.

On December 12, the Whitewater Register reported that cases had surged in Whitewater once again. Accounts were grim and included four young men who died within four days of each other in the local hospital and a young couple who died within 36 hours of one another, leaving children aged 3 and 18 months. Even the operator of the hospital, Mrs. Florence Wheeler, became sick, but, fortunately, she survived.

This second wave of the 1918 virus brought more stringent local public health measures. Houses with flu cases would be posted with “quarantine” signs, doctors were required to report all cases of flu within 24 hours, and theaters and churches could only have gatherings if they physically separated people. Dances, meetings, social events, and public entertainment were not allowed.

The peak of the second wave ended in January of 1919, but illnesses and deaths from the flu were reported into March. The pandemic in Wisconsin ended by April, but not before 103,000 had been infected and 8,459 died.

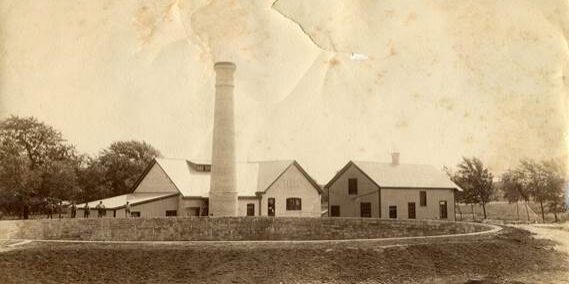

Footnote: The Whitewater hospital depicted in the photograph above was located near the modern water tower near Cravath and Wood Streets on the northeast side. At the time it was founded in 1909, it was common to keep hospitals on very large lots more toward the edge of heavy residential neighborhoods due to contagious diseases. The hospital burned in 1925 and no one was able to successfully start up another one due to the costs involved. Perhaps it was a factor that a 10-bed hospital had opened in Fort Atkinson in 1921. Additionally, the Great Depression started in 1929.

CORRECTION: Per Carol Cartwright, “after the hospital pictured burned, another small hospital operated at the corner of Main and Whiton Streets from 1925 to around 1940…The Historical Society has no photos of it.” This would have been at the southwest corner of Main and Whiton, apparently in the building that is still located at 907 W. Main Street. If anyone has any information about this hospital, please email whitewaterbanner@gmail.com.

— Our thanks to local historian Carol Cartwright, President of the Whitewater Historical Society, for this comprehensive report on the pandemic that occurred just over a century ago. As Ms. Cartwright stated, “That pandemic has a lot in common with today’s pandemic.” Surely, though, our current one will be curtailed with far less loss of life than the estimated 50 million deaths worldwide in 1918-19.

Note: The picture of a patient being loaded into an ambulance on the homepage, though taken during the pandemic, was not taken in Whitewater.

— Our Readers Share: We hope that you might have something that you’d be willing to share. Anything that’s been created by someone else should, of course, be credited, and you should ask their permission if you’re able. We cannot post copyrighted material without permission. We can’t guarantee that we’ll have space for all submissions, and contributions will be subject to editorial board approval. The one definite exclusion is anything politically oriented. Please indicate whether you’re willing for us to include your name as the submitter or if you prefer to remain anonymous. At least for now, no more than two submissions per person, please. Send to whitewaterbanner@gmail.com or click on “submit a story” near the top right of our homepage. Thanks for thinking about this!