(UW-W Press Release) After Paul Lauritzen arrived on the Whitewater State College campus in the fall of 1964 to start a special education program in its college of education, he soon found himself providing informal services for students with disabilities through the admissions office.

One day he took a call: “I have a student who uses a wheelchair. Can I admit them?”

Lauritzen said yes — mostly on determination and faith that the campus would make that student their own.

Lauritzen had kindred spirits in many places on campus.

One of them was Patrick Monaghan, an assistant chancellor and budget manager who helped Lauritzen apply for grants, a principal source of funding for support services and staff. Also in the Chancellor’s Office was Chuck Morphew, a vice chancellor and advocate whose wife, Jane, used a wheelchair as her primary source of mobility from having contracted polio.

With their support, dedicated services for students with disabilities began in 1968.

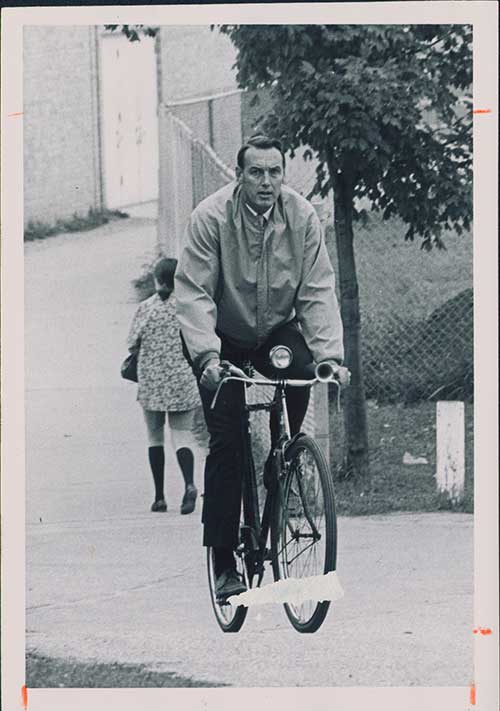

Then, during the 1970-71 academic year, a force of nature rolled across campus. John Truesdale — by all accounts a “character,” “a tireless advocate” and “a wonderful human being” — arrived to work at Whitewater through a joint project with the state Division of Vocational Rehabilitation, which was founded the same year. He began the college’s Disabled Student Services office, which served about 10 students.

“That’s something that I think this campus can be very proud of for a number of reasons,” said Truesdale. “Number one being that — well before there was any legal requirement to provide students with disabilities access to programs and services — UW-Whitewater had been doing for quite some time. And, in fewer than 30 years, the university was nationally recognized by student affairs professionals as one of the best programs of its kind in the nation.”

Truesdale and Monaghan succeeded at stitching inclusion for disabilities into the very fabric of the campus mission statement, which is the university’s spiritual governing principle. In 1973, campus administration adopted a mission for serving students with disabilities at UW-Whitewater, and the UW System Board of Regents approved it. That set the stage for new possibilities.

These days it isn’t uncommon to see a wheelchair user hop from their chair into the driver’s seat of a vehicle, disassemble their chair, toss it in the back and drive away. Truesdale promoted the teaching activities of daily living through physical therapy.

“That’s where you learn to be as independent as you can,” he said. “It doesn’t make sense to get a degree and not be able to work. We were going to provide services to help you live and work in a community just like everyone else.”

Truesdale is also credited with starting adaptive sports, including wheelchair basketball, and even coaching the team for eight years. Curb cuts and ramps for wheelchairs began to appear on campus and around the city well before it was required by the Americans with Disabilities Act, which was signed into law by President George H.W. Bush in 1990.

Wade James Fletcher, a business major who graduated in 1978, remembers how his wrestling coach, Willie Myers, worked with Truesdale to help keep the campus accessible. Myers had written his graduate thesis on how to prioritize removing architectural barriers to provide access to an institution.

“At UW-Whitewater, Willie was also the director of facilities management,” said Fletcher. In the winter, as part of a work-study project, Warhawk wrestlers worked to clear the snow and ice from sidewalks so that students with disabilities could safely and easily get around campus.

Truesdale’s department grew from a staff of one to more than eight professionals and 50 student employees. The mission to serve students with disabilities has been included in all updated campus mission statements and endorsed actively by every UW-Whitewater chancellor since 1973.

Looking back, Truesdale credits the success of the Center for Students with Disabilities to colleagues across campus — from faculty who see that an accommodation for a disability can improve learning for all students to the facilities worker who shovels the sidewalks.

By the 1990s, UW-Whitewater was recognized as a best-practices campus and a national model. The program was serving more than 300 students when Truesdale left in the early 2000s. Elizabeth Watson, who served as the director of the Center for Students with Disabilities for the majority of the time since Truesdale retired, remembers her first day as director, when former Chancellor Richard Telfer walked into her office. Telfer then was in transition from provost to becoming chancellor, and he wanted to meet Watson.

“He walked into my office to say ‘hi’ and it was about 20 minutes into the conversation before I realized this was someone important,” she said. “He said, ‘Do you think you could recruit 50 more students (with disabilities) a year?’”

“We left our comfort zone,” said Watson, as her staff began making recruiting visits to secondary schools. Some of the students they met had been told they never would go to college.

“These students became Warhawks. With CSD services and a campus-wide community, they went on to earn degrees.”

Meanwhile, Telfer and other administrators supported CSD with funding and put Watson at the table during architectural and design decisions. This was a revelation for Watson, who had been used to fighting for the spoils before coming to Whitewater. Accessibility, she said, is expensive. But the commitment was there.

“The university is creating thousands of disability advocates as they translate their college experience into the working world,” said Watson.

Over the years, the scope of the CSD mission has expanded to include services for students who are Deaf and hard of hearing, as well as students who have learning, psychological, chronic health and vision disabilities. The connections around campus extend into each of the colleges and to Warhawk Athletics. The center serves more than 1,200 students a year. And, in 2021, UW-Whitewater was named a Top 5 Mobility Friendly Campus in the nation by Mobility Magazine.

“It’s amazing to think about how the program has given so many graduates who happen to have disabilities the opportunity to live and work in Wisconsin communities,” said Truesdale. “And how UW-Whitewater has succeeded in carrying out its unique mission to develop and provide services for students with disabilities.”